Many, many moons before the White man came, a little Indian boy was left in the woods. It was in the days when animals and men understood each other better than they do now.

An old mother bear found the little Indian boy.

An old mother bear found the little Indian boy.

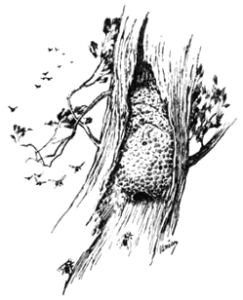

She felt very sorry for him. She told the little boy not to cry, for she would take him home with her; she had a nice wigwam in the hollow of a big tree.

Old Mother Bear had two cubs of her own, but she had a place between her great paws for a third. She took the little papoose, and she hugged him warm and close. She fed him as she did her own little cubs

.

The boy grew strong. He was very happy with his adopted mother and brothers. They had a warm lodge in the hollow of the great tree. As they grew older, Mother Bear found for them all the honey and nuts that they could eat.

From sunrise to sunset, the little Indian boy played with his cub brothers. He did not know that he was different from them. He thought he was a little bear, too. All day long, the boy and the little bears played and had a good time. They rolled, and tumbled, and wrestled in the forest leaves. They chased one another up and down the bear tree.

Sometimes they had a matched game of hug, for every little bear must learn to hug. The one who could hug the longest and the tightest won the game.

Old Mother Bear watched her three dear children at their play. She would have been content and happy, but for one thing. She was afraid some harm would come to the boy. Never could she quite forget the bear hunters. Several times they had scented her tree, but the wind had thrown them off the trail.

Once, from her bear-tree window, she had thrown out rabbit hairs as she saw them coming. The wind had blown the rabbit hairs toward the hunters. As they fell near the hunters, they had suddenly changed into rabbits and the hunters had given chase.

At another time, Mother Bear tossed some partridge feathers to the wind as the hunters drew near her tree. A flock of partridges went whirring into the woods with a great noise, and the hunters ran after them.

But on this day, Mother Bear’s heart was heavy. She knew that now the big bear hunters were coming. No rabbits or partridges could lead these hunters from the bear trail, for they had dogs with four eyes. (Foxhounds have a yellow spot over each eye which makes them seem double-eyed.) These dogs were never known to miss a bear tree. Sooner or later they would scent it.

Mother Bear thought she might be able to save herself and her cubs. But what would become of the boy? She loved him too well to let the bear hunters kill him.

Just then the porcupine, the Chief of the animals, passed by the bear tree. Mother Bear saw him. She put her head out the bear-tree window and called to him. He came and sat under the bear-tree window, and listened to Mother Bear’s story of her fears for the boy.

Just then the porcupine, the Chief of the animals, passed by the bear tree. Mother Bear saw him. She put her head out the bear-tree window and called to him. He came and sat under the bear-tree window, and listened to Mother Bear’s story of her fears for the boy.

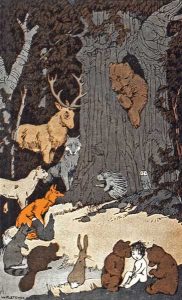

When she had finished, Chief Porcupine said he would call a council of the animals, and see if they could not save the boy.

Now the Chief had a big voice. As soon as he raised his voice, even the animals away on the longest trails heard. They ran at once and gathered under the council tree. There was a loud roar, and a great flapping of wings, for the birds came, too.

Chief Porcupine told them about the fears of Mother Bear, and of the danger to the boy.

“Now,” said the Chief, “which one of you will take the boy, and save him from the bear hunters?”

It happened that some animals were present that were jealous of man. These animals had held more than one secret council, to plan how they could do away with him. They said he was becoming too powerful. He knew all they knew,—and more.

The beaver did not like man, because men could build better houses than he.

The fox said that man had stolen his cunning, and could now outwit him.

The wolf and the panther objected to man, because he could conceal himself and spring with greater surety than they.

The raccoon said that man was more daring, and could climb higher than he.

The raccoon said that man was more daring, and could climb higher than he.

The deer complained that man could outrun him.

So when Chief Porcupine asked who would take the boy and care for him, each of these animals in turn said that he would gladly do so.

Mother Bear sat by and listened as each offered to care for the boy. She did not say anything, but she was thinking hard,—for a bear. At last she spoke.

To the beaver she said, “You cannot take the boy; you will drown him on the way to your lodge.”

To the fox she said, “You cannot take him; you would teach him to cheat and steal, while pretending to be a friend; neither can the wolf or the panther have him, for they are counting on having something good to eat.

“You, deer, lost your upper teeth for eating human flesh. And, too, you have no home, you are a tramp.

“And you, raccoon, I cannot trust, for you would coax him to climb so high that he would fall and die

.

“No, none of you can have the boy.”

Now a great bird that lives in the sky had flown into the council tree, while the animals were speaking. But they had not seen him.

When Mother Bear had spoken, this wise old eagle flew down, and said, “Give the boy to me, Mother Bear. No bird is so swift and strong as the eagle. I will protect him. On my great wings I will bear him far away from the bear hunters.

“I will take him to the wigwam of an Indian friend, where a little Indian boy is wanted.”

Mother Bear looked into the eagle’s keen eyes. She saw that he could see far.

Then she said, “Take him, eagle, I trust him to you. I know you will protect the boy.”

The eagle spread wide his great wings. Mother Bear placed the boy on his back, and away they soared, far from the council woods.

The eagle left the boy, as he had promised, at the door of a wigwam where a little Indian boy was wanted.

This was the first young American to be saved by an American eagle.

The boy grew to be a noble chief and a great hunter. No hunter could hit a bear trail so soon as he, for he knew just where and how to find the bear trees. But never was he known to cut down a bear tree, or to kill a bear.

However, many were the wolf, panther, and deer skins that hung in his lodge. The hunter’s wife sat and made warm coats from the fox and beaver skins which the hunter father brought in from the chase. But never was the hunter, his wife, or his children seen to wear a bear-skin coat.

Looking back at my upbringing, many common sense values were first introduced to me through fairy tales, fables and nursery rhymes. One of my fondest early childhood memories is my older sister and I sitting in my father’s lap while he read stories from the “Childcraft” story collection. I hope you will enjoy spending a few moments experiencing the wisdom of these timeless writings.

If you have any tales or fables you would like to see, leave a note in the comment section below.

Thanks and God bless.

Vince