From “Fairy Tales Told in the Bush”

By Sister Agnes

ong, long ago in the days when there were no schools, there lived a man and his wife and their only child. He was a bright, clever boy, and his parents were very ambitious for their dear boy, and wished him to become a great and renowned man. They saw that the children who could not read or write, but who just played all day long, had to go to work while still very young, and were generally so stupid that they could never earn much money; so they determined to let their boy have an education, and be able, later on, to have an easier life than they themselves had ever enjoyed. They worked early and late and saved every penny, even when their boy was still a baby, and by the time he was old enough to learn, they had saved enough money to pay a learned man who lived in the town to teach the boy. Boy he was always called, and I am very glad there is no other name for him, because of his bad ending.

ong, long ago in the days when there were no schools, there lived a man and his wife and their only child. He was a bright, clever boy, and his parents were very ambitious for their dear boy, and wished him to become a great and renowned man. They saw that the children who could not read or write, but who just played all day long, had to go to work while still very young, and were generally so stupid that they could never earn much money; so they determined to let their boy have an education, and be able, later on, to have an easier life than they themselves had ever enjoyed. They worked early and late and saved every penny, even when their boy was still a baby, and by the time he was old enough to learn, they had saved enough money to pay a learned man who lived in the town to teach the boy. Boy he was always called, and I am very glad there is no other name for him, because of his bad ending.

When Boy was fourteen years old, he knew so much about books that there was not a single book in the learned man’s library that he had not read. Oh, he was very clever and knowing, and he told his mother and father that he now knew enough to go and earn a good living. “In the morning,” said he, “I shall set out to make a fortune.”

Long before daybreak, the boy set out on his journey, carrying a bundle done up in a big red handkerchief. It contained a clean shirt, a pair of socks, a loaf of new bread, and a bottle of milk. His parents were very sad when he went away, but they knew he would never have any chance to become great and famous in the town where every one knew him as “the boy.”

Away trudged the boy, up hill and down dale, until at last, just before sunrise, he came to a hill where, as he imagined, cock had never crowed and man had never walked before. Tired and hungry, he sat down to eat his loaf and drink his milk, and, just as he had finished, a little old man dressed all in brown suddenly appeared before him. The boy rubbed his eyes to make sure he was not dreaming, for a minute before he had been alone; now, here was this funny little man looking at him. The little man wore knee-breeches and silk stockings, a cut-away coat, and a cocked hat, all of brown, and the funny thing was that the colour of his clothes matched the colour of his eyes and hair.

“Well, my boy,” said the old man, “you look surprised to see me.”

“Yes, sir, I am; I thought no one lived here.”

“Can’t people be in a place without living there? You yourself are here at present, but I suppose you don’t live here.”

“No, sir; I am going out into the world to make my fortune.”

“Just the boy I want. I am looking for a boy who will promise to do a little work for me for six months, and for that little work he is to get £50. Will you come and do it?”

“That I will,” cried the boy, jumping up gladly.

“Stay, though, there is one question I must ask first,” said the little old man. “Can you read or write?”

“Yes,” answered the boy proudly, “I can read anything in my tutor’s library.”

“Ah! then you won’t do for me, and I must go on my way in search of a boy capable of doing what I want, but unable to read or write.”

“Why do you want——” began the boy; but he was speaking to space, the little old man in brown had disappeared. Suddenly the boy formed a resolution. He would go home again, make himself look quite different, and come to-morrow morning to this same place, and then, if the little old man came—— Well, the boy had been taught to read and write, but he had not been taught to be truthful or honest. His parents thought that did not help people to get rich or famous.

Back he went to his home, and when he told his mother what he intended to do, she was quite pleased. “See,” she said to her husband, “how clever the boy is; this is what book-learning has done. No one else would think of such a clever trick.”

Next morning, at sunrise, there was a boy again sitting on the top of that distant hill, where the boy had breakfasted the day before. Indeed it was “the Boy,” although he looked quite different. He had dyed his fair hair and his eyebrows, making them look almost black, and he had rubbed the juice of a certain bark on his skin to make him seem dark. There he sat, a dark foreign-looking boy, eating his breakfast and impatiently waiting for the little old man to come again. He had not long to wait. How he came the boy never knew, but he suddenly knew he was not alone, and looking up saw the old man looking at him.

“Ah, a fair boy yesterday, and a dark one to-day. I hope there is more luck for me with the dark than there was with the fair. What are you doing here, boy?”

“I’m looking for work, sir,” answered the boy, trying not to show how delighted he felt.

“Good,” said the old man, “and I’m looking for a boy who wants work.”

“Will you engage me, sir?”

“Softly, softly, there are one or two things to speak about first. Can you read and write?”

“No, sir,” answered the boy, not even turning a shade paler under his dye, for you see he had never been taught to be truthful or honourable.

“Good again; then if £50 a year will suit you, you can come at once.”

Of course the boy said “Yes” to that, and the old man led him to a house just over the next hill, a pretty house standing in a big natural garden.

“Come in,” said the old man, unlocking the door, “come in and I’ll show you what you must do to earn your money.”

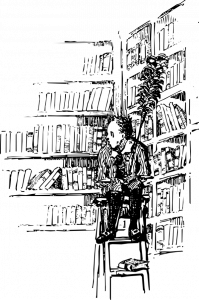

The boy was astonished to find that the house was really only one big room; each wall was covered with shelves from the ceiling to the floor, and each shelf was full of books. The boy was then told that he would be quite alone in the house, as his master meant to travel for six months. Usually he lived there by himself, but he had studied so much that his brain was tired, and he knew that if he wished to get really well and strong again, he must travel away, and not look at a book for six months. So he had hired the boy just to dust his beloved books in his lonely house, and, as it was so far away from people, he had to give a big sum of money, as wages, to get any one to stay there alone.

The boy stood looking around in astonishment. “Where am I to sleep?” he asked.

“Why, on that couch, of course,” said the old man; “you’ll find plenty of blankets under it.”

“And what am I to eat?”

“Ah! ah! ah!” laughed the old man, “trust a boy to make provision for that. There is, my boy, a wonderful secret connected with this house. When a certain magic word is pronounced, a table is lowered by invisible hands, and on the table you will find everything you wish to eat and drink. Now say it after me, ‘Corremurreplatyemurrepleuemurretimemurrejcherymurrepljeskuskiski.’”

Slowly the boy repeated the strange word after the old man, and, as he finished, there descended a table even as he had been told. On the table was a baked fowl, a duck, vegetables, puddings, tarts, cakes, sweets, and two or three kinds of drinks. Oh, these things were good! The boy soon knew that, and when he had eaten and drunk as much as he could, the man said he must get away as soon as possible, as he felt his brain could not stand the strain of even the backs of the books much longer.

“I know you can’t read and write, boy,” said the old man, “and yet I want you to promise me you won’t read a single word in these books, nor even open them.”

The boy promised readily enough, and then the old man went off. At first the boy worked at the dusting, never daring to open one of the books in case the old man should suddenly appear as he had done on the hill-top; but, as day after day passed, and there was no sign of him, he grew bold and began to read. What he read was very, very strange, stranger than anything he had ever heard of. Soon indeed he knew that his master must be the cleverest man in the world, for he learned from his books how to turn himself into any animal, and then to change back again into himself. How he longed to try it, but he dare not, because one condition was, that a person turning into an animal found a leather halter round his neck, and only a human being could undo it, so that he might turn back again to what he had been before.

Long before the six months were over, the boy was longing to go and try this wonderful unheard-of thing, but he dared not go until the old man came back, or he not only would have had to go penniless, but the old man might suspect him, and watch him and his actions.

At last, however, the little old man returned. “Have you kept your promise?” were his first words. “You have not read the books?” and the boy vowed and protested that he had not even opened the books. The old man examined his precious volumes, and, finding them in good order, paid the £50, and the boy then set out for his home. His father and mother could hardly believe he had earned so much money in such a short time.

“Easy come, easy go,” is a homely saying, and certainly “Boy’s” £50 went very easily indeed, and soon it was all spent. “You must go and earn some more money,” said his mother.

“Ah! ah!” laughed Boy, “not I; I’ve learned how to get money without working, no more working for me. I’ve learned how to turn myself into any animal I like. The worst of it is, though, if I change into an animal used by man, like the horse, cows and dogs, a halter will be around my neck, and I can’t change back again until the halter is taken off. Now, to-morrow is market day, and all the farmers will be in the town, so I’ll change myself into a bull, and you can take me to market and sell me, but remember to take the halter off my neck.”

“Never fear,” said his father, “I’ll remember.”

Early next morning, when Boy’s father went into the yard, there stood a beautiful black bull which he at once led off to the market. Quite a commotion was made by the fine bull.

“Come here,” cried the farmer who first saw it, “come here, and look at this prize bull.”

A crowd gathered around, and soon the farmers had made up their minds to buy it between them, as no one was rich enough to buy such a costly bull for himself alone. £1,000, and well worth it, they all declared. So five of them clubbed together and bought it. One farmer, who had a big strong stable, was to take care of the fine beast. Together they took the bull to the stable, saw it safely locked up, and the key put in the farmer’s pocket.

Next day the five owners brought some friends to see their prize, but, lo, the bull had disappeared. They looked at the fastenings of the door—nothing wrong—and there was no other way by which the bull could have escaped, so they all declared that the farmer had hidden the bull and meant to sell it secretly. Poor man, he was at once hurried off to prison. Where was the bull? Why, no sooner had the farmers locked the door, than the bull changed himself into a fly, and flew through the keyhole. When the boy’s father reached home, there was his son sitting by the side of the fire enjoying a meal, while his mother rocked herself from side to side, laughing at the trick he had played the farmer.

“A thousand pounds! now, if we had another thousand, we would never need to work again. Change yourself into another animal next market day, and I’ll sell you again.”

“No,” said the son, “we must wait awhile, there will be a great noise about the bull that has disappeared.”

And indeed there was a noise about it. Everybody’s tongue clattered so loudly that even the little old man in brown heard a whisper about it. “Ah,” thought he, “that boy has played me false. A bull could not disappear unless some one knew my magic secret. I must keep a watch on that town, and see if any other valuable animal comes to the market.”

After some time people forgot all about the strange disappearance of the bull, and, as the boy’s father continuously worried him to work the magic trick again, he at last consented.

This time it was a beautiful prancing horse that was seen and admired by the market people. £1,000 was asked for it. The little old man, disguised in a great cloak and turned-down hat, began to bargain for it, and soon the father had sold it, and had begun to take the halter off its neck.

“Stop,” cried the little man, “I bought that horse as he stood, the halter included.”

“No, no, only the horse,” said Boy’s father.

“How could I lead the horse away without a halter? but to stop all dispute you shall have another £100.” The little old man threw down the money, jumped on the horse and galloped away.

“I’ve caught you at last,” said he to the horse, “now I mean to kill you; liar and thief that you are, for such sins you must die.” The little old man in brown galloped the horse up hills, and down dales and across rivers, but the horse never seemed even to tire. “Well, as you won’t die in one way you must in another. I shall have a goad made in such a way that every time I strike you with it blood will flow.”

At the first blacksmith’s to which he came, he stopped and called aloud for the smith to come out. Out came the smith, holding a heavy hammer in his hand, and the little old man in brown gave his directions for the goad; but the smith was not clever, so the old man had to get down, and go into the smithy to draw a plan of what he wanted made. The horse was left in charge of a boy. “Take the halter off my neck.” The boy in charge was so surprised to hear a horse speak that he obeyed, and the horse at once scampered off.

“Hey, mister, mister, your horse is running away.” These words brought the little old man out very quickly; sure enough there was the horse some distance off, galloping as fast as he could go. The old man changed himself into a horse and galloped after him. Of course there was no one to place a halter on him, so there was no halter to take off, and he could change again as soon as he wished to. The fresh horse soon gained upon the tired one.

“Dear, dear, this will never do, I must dodge him. I’ll change into a hare and sneak off into the bushes,” thought the boy; but no sooner had the boy become a hare than the old man became a greyhound, and began to get very close to him indeed. “Oh, dear! he is gaining on me, I shall change into a bird, and fly into the trees;” but no sooner had the boy become a little bird than the old man became a hawk and got closer still.

“Look!” cried a lady who sat at the window in her room, “look at the hawk chasing that poor little bird.” Quickly she opened the window, and the little bird flew in. To her astonishment it changed at once into a ring, and, lo, there it was on her finger!

A knock was heard at the door. “Come in,” said the lady. In came a little old man dressed in brown.

“Madam, I have lost a little bird; it was being chased by a hawk; it flew in here.”

“Yes,” answered the lady; “a strange thing happened; no sooner had it flown in here than it became a ring on my finger.”

“Madam, I claim my property,” said the little old man, stretching out his hand for the ring.

She took off the ring sadly, but it slipped from her fingers and rolled into the passage.

“What shall I do?” thought the boy. “I know, I’ll turn into a great bundle of straw, and crowd him out of the place.” You see, he was such a selfish boy he never even thought about the lady who had allowed him to fly into the room.

The lady was horrified to see the door filled up with straw; but, lo! the little old man at once turned himself into a donkey, and began to eat the straw. At every mouthful he of course ate what was really a piece of the boy, and the boy knew he must soon die at that rate. Hurriedly the boy changed himself into a mouse, but, alas! there was no mouse-hole for him to run and hide in, and before he could reach the door, the cat that belonged to the lady saw him, pounced upon him, and ate him up.

So that was the end of the boy who tried to get rich by stealing and lying. You might think that the £1,100 the old man had given the father made him a rich man for life. Not so, the neighbours and he soon spent it in gambling and drink, and in a short time he was as poor as he had been before his son began practising his magic tricks.